A Sound, Basic Document

By Sanjay Raman Sinha

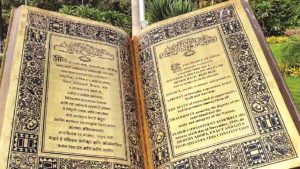

The guiding and governing principles of the Indian republic are enshrined in the Constitution. It is a living, organic document which has evolved with the passage of time, facing tough social and political challenges. Seventy-five years of Independence and 72 years of constitutional culture are a testimony to the spirit of India.

Justice MN Venkatachaliah, former chief justice of India and patron-in-chief of India Legal, reminisced: “I had the blessing and good fortune to stand witness to the great events related to the birth of our republic and its inspiring journey of 75 years. Today, India has a place of pride in the comity of nations. When our great leaders decided to make India a parliamentary democracy on the republican model with universal adult franchise, the western press was almost derisive and cynical about its success. How can 330 million people without education manage the sophistication of modern parliamentary democracy? For this, the credit must go to the common man: the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker. It was the same western press that later praised the Indian democracy as robust, but added that it was the rowdiest!’’

As the republic traversed 75 years, it witnessed a flux of ideas and events which tested the rigorousness of the Constitution. Whenever there was a conflict between the legislative statutes and the basic values of the Constitution, it was the judiciary which resolved it by interpreting the Constitution, all the while preserving its soul.

In the Golaknath and Kesavananda Bharati case, the judiciary propounded the basic structure doctrine and created internal safeguards which not only preserved the sanctity of the Constitution but of the individual as well.

Prof Upendra Baxi, eminent law scholar, said: “I believe that the judiciary safeguarded certain provisions of the Constitution which encapsulate its spirit. For example, some essential provisions are encoded in Article 14 and Article 17 which relate to equality and abolition of untouchability. Such provisions can’t be tampered with. They form the part of the basic structure of the Constitution and their inviolability was affirmed in the 1973 basic structure judicial pronouncement.’’

In Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala, Justice SM Sikri gave an illustrative list of features that qualified as a basic structure of the Constitution. This includes supremacy of the Constitution, separation of powers, republican and democratic forms of government, parliamentary democracy, secularism, federalism, fundamental rights, mandate to build a welfare state and unity and integrity of the nation amongst others. Several cases thereafter have added to the list or have interpreted existing features in novel manners to exercise the power of judicial review.

The Kesavananda Bharati judgment holds that Article 368 is shaped by the philosophy that every generation should be free to adapt the Constitution to the social, economic and political conditions of its time. However, to shield the sanctity of the Constitution, the judiciary has evolved the basic structure doctrine. Efforts of the executive to tamper with the core ideas of the Constitution have failed by virtue of this doctrine.

However, there is no definition for basic structure in the Constitution or law books. Is this a shortcoming? Should it be more clearly defined?

Prof Ranbir Singh, former vice chancellor of National Law School, Delhi, explained: “Being a judicial innovation, the lack of a clear and unambiguous definition in the text of the law is not surprising. Nevertheless, it would not be in the interest of a deliberative and inclusive democracy to have an exhaustive list of features which could be listed as a basic structure of the Constitution. The same will necessarily have to be interpreted in the social, political and constitutional contexts of the time.’’

The judiciary is often criticised for indulging in judicial overreach or judicial adventurism. However, Article 142 provides discretionary power to the Supreme Court to do complete justice, and hence, judicial activism may be held valid. Yet, under the doctrine of separation of powers, judicial initiative in policy matters is a breach into the executive arena. Often, it is a case between judicial activism vs executive mis-action/in-action. Prof Baxi said: “The question is not of judicial overreach, but of executive underreach. Overreach is not a problem. The Constitution should reach each and everyone.”

Over the years, judicial activism has increased confrontation with the government. As often in policy matters, when the government overlooked or ignored basic concerns of the citizens, the judiciary acted as a sentinel of human rights and initiated corrective measures via judicial fiats or instructions.

Dr Ranbir Singh explained: “The Supreme Court has long affirmed the view that separation of powers forms a part of the basic structure of our Constitution. Nevertheless, it is also true that the judiciary often oversteps its boundaries. The inherent contradictions in judicial appropriation of roles that are traditionally vested with the executive or the legislature can best be resolved using a two-pronged approach. The first prong should be that of self-imposed judicial restraint. Ideally, courts should not overstep their boundaries by entertaining issues which are subject matters of extensive empirical research and which require consideration of multiple perspectives—both of which may not always be readily available with the Court. The second prong must include the development of procedures that must be followed by the judiciary in exercising its power of judicial review, especially under its PIL jurisdiction. Such procedures must ensure that the exercise of such power is fair, transparent and judicious.”

It is interesting to note that though the Constitution makers held the document sacrosanct, they nevertheless included a provision to amend it. The process is defined in Article 368. “The denial of power to make radical changes in the Constitution to the future generation would invite the danger of extra Constitutional changes of the Constitution,” wrote Justice YV Chandrachud in the Kesavananda verdict.

Jawaharlal Nehru had spoken in the same vein: “While we make a Constitution which is sound and as basic as we can, it should also be flexible.” It was not in vain that Justice YV Chandrachud who had written his Kesavananda verdict in favour of Parliament’s unlimited power to amend the Constitution, later said he was entitled to change his views. The ADM Jabalpur verdict is a case in point. It held that declaration of emergency and suspension of fundamental rights can’t be challenged in the courts.

Historically speaking, there were two instances to rewrite or review the Constitution; one by the Congress and the other by the NDA. Though both efforts came to naught, the exercise carried a message.

Eminent journalist and Constitution expert Ram Bahadur Rai said: “There were two efforts aiming for different goals. The Sardar Swaran Singh Committee was set up by the Congress in 1976 and on the basis of its recommendation, the 42nd amendment was effected. The group close to Indira Gandhi floated three ideas: committed bureaucracy, committed judiciary and committed political party. These ideas led to a dictatorial and totalitarian regime. The 42nd amendment is a crude rewriting of the Constitution. The National Commission to review the working of the Constitution (NCRWC), also known as Justice Venkatachaliah Commission, was set up by a resolution of the NDA government led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee on February 22, 2000. The government stated in Parliament that the exercise was aimed at reviewing the Constitution and was not intended at changing its basic structure. The report was submitted, but till date, no action has been taken on it.’’

The Constituent Assembly has been especially attentive to the needs and rights of the underprivileged. The Constitution provides for special rights to both linguistic and religious minorities. It uses the term “minority” without defining it. However, affirmative action for socially underprivileged and “backward classes’’ is included in the Constitution. It was believed that time would erase from mass memory caste-based inequalities.

Justice Venkatachaliah asserted: “Every Indian has to come up within himself enduring values of liberty, equality fraternity and justice. They are not merely emotional ideas. Acharya Kripalani in the Constituent Assembly debates said that these are mystic concepts and shouldn’t be treated as mere contentious legal issues and ideas. Our generation has a great opportunity and moral duty to build a prosperous and happy India. Each Indian should be proud. Nothing less is acceptable. What is important is our commitment to social contract.’’

To actualise these “mystic concepts’’ of equality, affirmative action was envisaged. Reservation in jobs and educational institutions were put in place. To remove vested groups, the concept of creamy layer was propounded. Decades later, reservation is still a contentious issue. Recently when the Supreme Court upheld the validity of 10% reservation for the economically weaker section under the 103rd Constitutional Amendment, a national debate ensued.

Ram Bahadur Rai said: “It is an accepted fact that caste based economic backwardness exists. There is also another fact. Many from the upper castes also suffer from economic deprivation. They also need affirmative action to improve their lot. There should be no vested interest in reservation’’

Under constitutional law, women have equal rights as men so as to enable them to take part effectively in the administration of the country. Dr BR Ambedkar had said: “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved”

The Constitution not only grants equality to women, but also empowers the State to adopt measures of positive discrimination in its favour. There were 15 women in the Constituent Assembly as well. They were freedom fighters, lawyers, reformists and politicians and they spoke in the favour of women, but still their representation in society is low. Even now, the Supreme Court has to intervene in matters like women’s recruitment in the army, property rights, conjugal rights and sexual rights.

Prof Raghav Sharan Sharma, a writer and Constitution expert, said: “Without demolishing old restrictive social structures, neither Dalits nor women can get justice. The old structure is feudal in nature and till the time this is shattered, no growth or justice is possible for this segment of citizens. Policy implementation for furtherance of their cause has always a matter of convenience and not a matter of conviction.”

Another conflict point is the concept of secularism. The Preamble of the Constitution holds India as a sovereign, socialist, democratic republic. The terms socialist and secular were added to it by the 42nd amendment. In the Indian context, secularism means that the State should be equidistant from all religions; that the Republic shall not have any State religion. However, the resurgence of Hindu nationalism has sought to redefine this premise.

Prof Sharma said: “Subhash Chandra Bose had held that religion and politics are separated and unifying the two will not be acceptable by the Constitution. Nehru had also endorsed his brand of secularism which separated the State from religion. But both visualised religious coexistence. The aftermath of Partition saw communal riots and these clashed have continued till this day. However, what is heartening is that people are approaching courts for justice rather than killing each other. The policy of appeasement followed by political parties has added fuel to fire.”

Another area of concern is centre-state relationship. The Constitution has called the republic a quasi federal union of states. Dr Ambedkar, while introducing the draft Constitution noted: “The Union at the centre and states at the periphery are each endowed with sovereign powers to be exercised in the field assigned to them by the Constitution.”

While the sanctity of individual states is assured, the primacy of the centre is also affirmed. However at the operational level, the trend towards centralism has created a conflict between the centre and states. Are provisions in the Constitution adequate to handle the issue of centre-states relationship?

Dr Ranbir Singh explained: “The reason behind having a strong centre with well-defined features for states is what the diversity in India is all about—be it on the grounds of regionalism, linguistics, caste, religion, political aspirations, etc. The states were given a large area of administration and wide discretion in decision making.

At the same time, a strong centre was required to ensure inter-state cooperation and security of national interests. Despite this, we have recently seen some fault lines in centre-state ties in constitutional registers, be it water disputes or demands for reservation related amendments. In this context, there is often little that formal provisions in the Constitution can do. The words of Dr Ambedkar from his final speech in the Constituent Assembly are extremely pertinent in this regard: ‘…however good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot. However bad a Constitution may be, it may turn out to be good if those who are called to work it, happen to be a good lot.”

Today as India celebrates its commitment to the Constitution, social justice and equitable economic development envisaged by the Constitution framers are out of reach.

Justice Venkatachaliah said with concern: “Today, after 75 years, the nation is poised at a very sensitive point of its history. Science and technology has opened new possibilities, which if not properly utilized, can create enormous inequalities. Education, healthcare, skill development and livelihood for a vast majority of our fellowmen are critical issues. It is somewhat ironic that the common man has access to internet, mobile phones and television, but not to potable water. Even for the rich in rural areas, flush toilets are a luxury. The world’s GDP is said to be $83 trillion. The US has 21% percent share, while India has just 3%. Building the nation’s physical wealth and prosperity is of primary concern.’’

As India marches to fulfill its dreams of an equitable and just society, we should heed the words of Dr Ambedkar: “If we wish to maintain democracy not merely in form, but also in fact, we must hold fast to constitutional methods of achieving our social and economic objectives.”

The post A Sound, Basic Document appeared first on India Legal.

from India Legal https://ift.tt/qpU5vAo